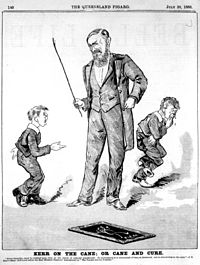

Twenty years ago, when I was completing my doctorate, my school law prof contended that we (teachers and administrators) regularly denied students their fundamental rights when we were dealing with discipline issues. His argument was that when a student was called into the office to account for her or his behaviour, there was such a power imbalance that there was no way that the child would get a fair and impartial hearing. Administrators like me straddled the roles of judge, jury, and executioner.

This stuck with me over the years and I have always tried to provide the student with an adult advocate (usually one of our counsellors) in the room to ensure that the student felt that someone was looking out for their interests. Having said that, I increasingly have the feeling that the power imbalance that seemed so clear to that academic back in the 1990s has actually shifted in the other direction. At the end of the second decade of this century, it tends to be the student who holds a majority of the cards in these discussions. To begin with, it has been my experience that in the brief time between most such incidents and the school's response, the student has already articulated their planned defence and version of events either by phone call or text to a parent. In this version of recent history, the accusing students become liars, the witnessing teacher becomes a biased bully, and the blundering Head of School (that would be me) has clearly been so misinformed that he assessed dire consequences (such as staying in at lunch) on the perpetrator rather than on those conniving victims!

Two recent illustrative events stick in my mind. In one case, a student flattened another with a roundhouse punch on the school grounds. He was given a one day in-house "suspension" where he had to work on assignments in the Student Services office, and had breaks and lunch separated from his peers. His grandfather came in to see me, steamed that there had been no equivalent consequences for the victim whose role in the incident amounted to being in the wrong place at the wrong time. The version of events that the grandparent told me were so far from reality that it was laughable, but the bottom line was that he refused to send the student back to school until the suspension was lifted. After spending three days home with the student, and no capitulation on our part, the grandparent relented and the student returned and received his consequences. A few days later I received an email from the grandfather in which he told me that after two days of questioning the student had finally admitted that his attack was unprovoked. There was no apology in the email, only a question about the school's inability to prevent his grandson from hitting someone else - "where were the supervisors?".

The second involved a group of four elementary boys who decided that it would be a great idea to urinate into a bottle, fill a squirt gun with the liquid and terrorize their friends on the playground. Fortunately, one of our teachers got wind of the plan and intervened between the filling and the shooting stages thereby thwarting the boys from carrying out their campaign. Three out of four families responded as you would expect - they were mortified, supported the school's consequences and imposed far more stringent ones at home. The fourth blamed the other students, the school (who had admitted such hooligans as their child's friends) and the teacher who had accused their innocent bystander son. They subsequently withdrew their child in search of an institution with far less draconian codes of conduct.

Most good schools have clearly defined behavioural expectations for students and faculty. These Codes of conduct run the gamut from norms of dress, acceptable tech use, and inappropriate language to harassment, assault and illegal activity and everything in between. Published and shared with staff, students and parents, they should form a clearly understood Social Contract for the school community and the consequences for ignoring them should be well-defined and consistently applied.

To be honest, most students have a pretty well developed sense of natural justice. They don't like to see others get away with something without consequences but, like all of us, would rather that they personally escaped accountability if at all possible. That is all part of being a child or adolescent. It is our job as the adults in the room (teachers, parents, administrators) to not only enforce social norms and expectations, but also to ensure that the young people in our care understand that they have to take responsibility for their actions and to suffer whatever consequences that are assigned as a result. This is not punishment, it is a life lesson towards becoming a responsible and socialized adult.

The alternative for parents is to expect that the next text or phone call home from your child might be to post bail!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed